WORD

document HERE

Within a decade Australians will be able to find out how good their genes are at fighting disease, which environmental risks they are susceptible to and steps they should take to prevent the onset of ill-health. And by the turn of the century it will be commonplace to have a bad combination of genes repaired to avoid disease.

'Then, Now…Imagine', a new report compiled by Research Australia in consultation with 10 of the country's leading health and medical researchers including two Nobel Prize winners and four Australians of the Year, predicts individual gene profiling from blood samples will revolutionise healthcare within ten years.

2006 Australian of the Year, Professor Ian Frazer, who discovered the technology that led to the newly released cervical cancer vaccine, said the upshot will be the ability to develop personalised healthcare plans – a roadmap for health from the day of birth.

"Doctors will be able to predict what health problems we might get so we can take appropriate precautions. They will also be able to assess what treatments will work best on an individual basis to achieve optimum health results. Long-term it will be possible to avoid certain diseases altogether through gene therapy," he said.

Sponsored by MBF, the report has been released by Research Australia to commemorate "Thank You" Day (14 November 2006), Australians' annual opportunity to send personal messages of appreciation to medical researchers whose work is special to them via www.thankyouday.org or 0428THANKS. "Thank You" Day is held each year with the support of the Macquarie Bank Foundation.

Therapeutic vaccines are also well advanced in development and involve re-educating the immune system to recognise cancer cells as intruders and attack them.

And over the next few decades we are likely see vaccines for many viral infections like HIV/AIDS and Hepatitis C, and for major diseases like diabetes. In fact Melbourne's Diabetes Vaccine Development Centre is about to start clinical trials for a new vaccine for Type 1 Diabetes.

This technology will also be applied to other disabilities. We will be able to reconnect electrical wiring in damaged spinal columns, stimulate nerve growth and allow messages to be relayed to the brain. Further into the future, this could ultimately allow quadriplegics and paraplegics to walk again. Other applications are likely to include correcting the faulty circuits that create epileptic episodes and creating transport systems for slow release of insulin to diabetics.

Professor Peter Doherty, Nobel Laureate 1996 – Discovered that T-cells, the foot soldiers in our bloodstream, were expert at killing cells that had viruses locked inside. This has led to new and better vaccines, healthy organ transplants and better treatment of conditions like Multiple Sclerosis and Diabetes.

Professor Ian Frazer, Australian of the Year 2006 – Gained international fame for developing the world's first vaccine to combat cervical cancer.

Dr Fiona Wood, Australian of the Year 2004 - Headed up the team of doctors who treated the burns victims of the 2002 Bali bombing. Her use of 'spray on skin' sped up the recovery process for those who had suffered horrific burns.

Professor Fiona Stanley, Australian of the Year 2003 - With Carol Bower, as part of an international collaboration, discovered the link between folate intake and spina bifida. This led to women being advised to increase folate intake before and during pregnancy and supplementation of some foods with folate.

Sir Gustav Nossal, Australian of the Year 2000 – Discovered the magic 'one cell-one antibody' rule which led to the development of effective new therapies for heart disease, breast cancer and severe arthritis.

Professor Terry Dwyer - Led the team which proved the link between a baby's sleeping position and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. They found that a baby sleeping on its stomach has ten times the risk of SIDS than babies who sleep in other positions.

Professor Graeme Clark - Pioneered the multiple-channel cochlear implant which has brought hearing and speech understanding to tens of thousands of people with severe-to-profound hearing loss in more than 70 countries.

Professor Judith Whitworth – Discovered how steroids raise blood pressure. Former Chief Medical Officer for the Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services and current Chair of the World Health Organisation (WHO) Global Advisory Committee on Health Research.

Professor John Shine – First to clone a human hormone gene and discovered a gene sequence, the Shine-Dalgarno sequence, which is important for the control of protein synthesis. Former Chair of the National Health and Medical Research Council and current member of the Prime Minister's Science, Engineering & Innovation Council.

Research Australia is a unique national alliance of more than 180 member and donor organisations with a common mission to make health and medical research a higher national priority. For more information on Research Australia visit www.researchaustralia.org.

"Plastic surgery patients are taking a proactive approach in making themselves happier by improving something that has truly bothered them," said Bruce Freedman, MD, ASPS Member Surgeon and study author. "While we are not saying that cosmetic plastic surgery alone is responsible for the drop in patients needing antidepressants, it surely is an important factor."

In the study, 362 patients had cosmetic plastic surgery – 17 percent or 61 patients were taking antidepressants. Six months after surgery, however, that number decreased 31 percent, down to 42 patients. In addition, 98 percent of patients said cosmetic plastic surgery had markedly improved their self-esteem.

All of the patients, who were primarily middle-aged women, had an invasive cosmetic plastic surgery procedure such as breast augmentation, tummy tuck or facelift. The authors did not identify any other major life changes that may have affected patients' use of antidepressants.

"We have just begun to uncover the various physical and psychological benefits of plastic surgery," said Dr. Freedman. "By helping our patients take control over something they were unhappy about, we helped remove a self-imposed barrier and ultimately improved their self-esteem."

The American Society of Plastic Surgeons is the largest organization of board-certified plastic surgeons in the world. With more than 6,000 members, the society is recognized as a leading authority and information source on cosmetic and reconstructive plastic surgery. ASPS comprises 94 percent of all board-certified plastic surgeons in the United States. Founded in 1931, the society represents physicians certified by The American Board of Plastic Surgery or The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada.

Note: The study "Cosmetic Surgery and the Use of Antidepressant Medication" is being presented in electronic format, Sunday, Oct. 8 – Tuesday, Oct. 10, at the Moscone Convention Center, San Francisco. Reporters can register to attend Plastic Surgery 2006 and arrange interviews with presenters by logging on to www.plasticsurgery.org/news_room/Registration.cfm or by contacting ASPS Public Relations at (847) 228-9900 or in San Francisco, Oct. 7-11 at (415) 905-1730.

The new research comprehensively and convincingly makes the case that the small skull discovered in Flores, Indonesia, in 2003 does not represent a new species of hominid, as was claimed in a study published in Nature in 2004. Instead, the skull is most likely that of a small-bodied modern human who suffered from a genetic condition known as microcephaly, which is characterized by a small head.

"It's no accident that this supposedly new species of hominid was dubbed the 'Hobbit;'" said Robert R. Martin, PhD, Curator of Biological Anthropology at the Field Museum and lead author of the paper. "It is simply fanciful to imagine that this fossil represents anything other than a modern human." The new study is the most wide-ranging, multidisciplinary assessment of the problems associated with the interpretation of the 18,000-year-old Flores hominid yet to be published. The authors include experts on:

Significantly, the second most recent publication to conclude that the "Hobbit" was microcephalic--another multidimensional study that was published in the September 5, 2006, issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences--includes a co-author who was also a co-author of the original publication in Nature. That scientist, R.P. Soejono of the National Archaeological Research Center in Jakarta, Indonesia, now writes that the Flores hominid was microcephalic rather than a new hominid species.

Rewriting science

The starting point for the new research in Anatomical Record was the realization that the brain of the Flores skull (at 400 cc, the size of a grapefruit and less than one-third of the normal size for a modern human) is simply too small to fit anything previously known about human brain evolution. In addition, the stone tools found at the same site include types of tools that have only been reported for our own species, Homo sapiens.

Brain size of the Flores hominid, originally called Homo floresiensis, is known only from the main specimen discovered there, the LB1 skeleton. Skeletal fragments have been attributed to eight other individuals, but nothing can be said about their brain sizes. (They are small-bodied, but that has never been at issue.)

The new exhaustive research shows that the LB1 brain is simply too small to have been derived from H. erectus by evolutionary dwarfing, as was claimed by those wh o

discovered it. In fact, the size

of the brain corresponds very closely to the average value for modern

human microcephalics. Microcephaly is a term that covers many

conditions. There are more than 400 different human genes for which

mutations can result in small brain size. Accordingly, there is a

correspondingly wide range of different syndromes that are recognized

in clinical practice. Many syndromes involve pronounced deficits

("low-functioning microcephaly"), but some have milder effects

("high-functioning microcephaly"), permitting survival into adulthood

and a surprising degree of behavioral competence in certain cases.

Microcephaly is often associated with severely reduced stature, but

some microcephalics have relatively normal body size.

o

discovered it. In fact, the size

of the brain corresponds very closely to the average value for modern

human microcephalics. Microcephaly is a term that covers many

conditions. There are more than 400 different human genes for which

mutations can result in small brain size. Accordingly, there is a

correspondingly wide range of different syndromes that are recognized

in clinical practice. Many syndromes involve pronounced deficits

("low-functioning microcephaly"), but some have milder effects

("high-functioning microcephaly"), permitting survival into adulthood

and a surprising degree of behavioral competence in certain cases.

Microcephaly is often associated with severely reduced stature, but

some microcephalics have relatively normal body size.

Because the LB1 skeleton is clearly that of an adult, it should obviously be compared with "high-functioning" modern human microcephalics rather than with "low-functioning" microcephalics who died early. The new study shows that skulls and brain casts from two modern human microcephalics who survived into adulthood are actually quite similar to those of the LB1 specimen. This supports the likelihood that LB1 was microcephalic.

Another area of controversy concerns the stone tools discovered in association with the Flores fossils. Initially, the discoverers claimed that the tools were sophisticated, as indeed they are. More recently, continuity has been claimed with tools from Mata Menge on Flores that are purportedly 800,000 years ago. This is simply implausible, according to the authors of the new research.

"Nobody has even claimed cultural continuity in stone tool technology over such a long period (800,000 to 18,000 years ago)," Dr. Phillips said. "To do so ignores the significance of tools found with the LB1 skeleton that were made with the advanced prepared-core technique, otherwise confined to Neanderthals and modern humans."

There has been too much media hype and not enough sound scientific evaluation surrounding this discovery, Dr. Martin concluded. "Science needs more balance and less acrimony as we continue to unravel this discovery."

Robert D. Marin, PhD, Curator of Biological Anthropology at The Field Museum, has devoted his career to studying primate development and evolution. In his quest to achieve a reliable reconstruction of primate evolutionary history, Dr. Martin has studied an extensive array of characteristics in the living species, including anatomical features, physiology, chromosomes and DNA. Dr. Martin has been particularly interested in the brain and reproductive biology, as these systems have been of special importance in primate evolution. With skeletal features, it is possible to include the fossil evidence and thus to include geological time in the picture. By studying living primates in the field in the forests of Africa, Madagascar, Brazil and Panama, Dr. Martin has also been able to include behavior and ecology in an overall synthesis. That synthesis was first presented in his textbook Primate Origins and Evolution, published by Princeton University Press in 1990. Since then, he has been working on refinements in several different directions. Photo by John Weinstein, Courtesy of The Field Museum (Negative # GN90075_36Ac)

• Jim Phillips

James Phillips, PhD, Departments of Anthropology at the University of Illinois at Chicago and the Field Museum, is an expert on stone tools. Initially, the discoverers of the Flores fossils claimed that the tools found in association with the fossils were sophisticated, as indeed they are. More recently, continuity has been claimed with tools from Mata Menge on Flores that are purportedly 800,000 years ago. This is simply implausible, according to the authors of the new research. "Nobody has even claimed cultural continuity in stone tool technology over such a long period (800,000 to 18,000 years ago)," Dr. Phillips said. "To do so ignores the significance of tools found with the LB1 skeleton that were made with the advanced prepared-core technique, otherwise confined to Neanderthals and modern humans."

"People often think breast reduction is an elective cosmetic procedure, but the majority of women seeking this surgery are legitimately debilitated by their breasts," said Michael Wheatley, MD, ASPS Member Surgeon and paper co-author. "The criteria most insurance companies use is not supported by medical literature and eliminates a large number of women from coverage, forcing them to fend for themselves."

Most insurance companies require patients to exhibit specific signs and symptoms prior to approving breast reduction as medically necessary. The amount of tissue removed to relieve symptoms associated with overly large breasts is the most controversial of all insurance criteria.

The authors reviewed the breast reduction policies of 87 health insurance companies. Despite contrary medical studies, 85 companies require a minimum amount of tissue to be removed to cover the procedure – 49 of these companies require a minimum amount to be removed independent of the patient's height and weight.

According to published studies, although most patients have a one-and-a-half to two cup size reduction, the amount of tissue removed, body weight, level of obesity, or bra cup size do not affect the benefits that patients receive from breast reduction.

Many insurance companies require that patients exhibit all of the following symptoms to receive coverage for breast reduction: back, neck, shoulder, and arm pain; rashes; bra strap grooves; and numbness in the upper torso. The authors found that while most patients suffer from many of these symptoms, rarely do they exhibit all.

According to Dr. Wheatley, most patients are women between 30 and 50 years old who have had upper skeletal pain for years. Many of them have tried various treatments, including physical therapy and pain medications, to manage the pain before turning to breast reduction. However, many of these women are still turned away by their insurance companies.

According to ASPS statistics, more than 114,000 breast reductions were performed in 2005.

The American Society of Plastic Surgeons is the largest organization of board-certified plastic surgeons in the world. With more than 6,000 members, the society is recognized as a leading authority and information source on cosmetic and reconstructive plastic surgery. ASPS comprises 94 percent of all board-certified plastic surgeons in the United States. Founded in 1931, the society represents physicians certified by The American Board of Plastic Surgery or The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada.

Note: The study "Reduction Mammoplasty: A Review of Managed Care Medical Policy Criteria" is being presented Sunday, Oct. 8, 3:04 p.m., at the Moscone Convention Center, San Francisco. Reporters can register to attend Plastic Surgery 2006 and arrange interviews with presenters by logging on to www.plasticsurgery.org/news_room/Registration.cfm or by contacting ASPS Public Relations at (847) 228-9900 or in San Francisco, Oct. 7-11 at (415) 905-1730. VIRGINIA BEACH, VA (October 9, 2006) -- The long-lived naked mole-rat shows much higher levels of oxidative stress and damage and less robust repair mechanisms than the short-lived mouse, findings that could change the oxidative stress theory of aging.

The new study comparing the naked mole-rat, which has a life span of 28 years, and the mouse, which has a lifespan of three years, will be presented Oct. 8 at The American Physiological Society conference, Comparative Physiology 2006: Integrating Diversity. The results fly in the face of the oxidative stress theory of aging, which holds that damage caused by oxidative stress is a significant contributor to the aging process.

Under this theory, naked mole-rats should be better at preventing or repairing oxidative stress than their much shorter-lived cousin, the mouse. The study, "High oxidative damage levels in the longest-living rodent, the naked mole-rat," was done by Blazej Andziak and Rochelle Buffenstein, of The City College of New York, Timothy P. O'Connor, of Weill Medical College of Cornell University, and Asish P. Chaudhiri and Holly Van Remmen of the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio. The study was presented during a poster session on October 8.

Don't toss the oxidative stress theory of aging out the window just yet, but prepare to modify it, said Buffenstein, the senior author. Her team suspects that the naked mole-rat's longevity stems from its ability to defend against acute bouts of oxidative stress. That is, the kind of oxidation that happens because of an unusual occurrence rather than the kind that happens as a result of normal aerobic respiration.

For example, when hydrogen peroxide is added to a culture containing naked mole-rat fibroblast cells, they remain viable and appear to repair the acute damage more rapidly than shorter-lived animals, explained Buffenstein.

What is old age?

We know that all organisms age and die. It's such an inevitable course of events that most of us spend more time thinking about how to hide the wrinkles and gray hair than we do about what our cells are actually doing to usher us to the end. Physiologists are looking at molecules and cells to understand this process.

One way to look at aging is to compare closely related organisms with different life spans. That's why it made sense to compare mole-rats and mice: They're the same size and they're rodents, but the mole-rat lives to 28 years, about nine-times longer than the mouse.

"Mole-rats must have something happening at the biochemical level to allow them to do this," said Andziak, the study's lead author. Specifically, he wanted to see if oxidative stress could explain the difference.

Oxidative stress occurs during metabolism when oxygen (O2) splits into single oxygen atoms, known as free radicals. These oxygen atoms may circulate by themselves, or combine with other atoms and molecules to form reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS can damage DNA, lipids and proteins thus impairing normal cellular function. Antioxidants help to neutralize ROS, thus restricting the potential of ROS to damage biological molecules.

Mole-rat has more oxidative stress

The study compared two-year-old naked mole-rats to four-month-old mice. The researchers chose those ages so that the animals would be equivalent ages relative to their maximum lifespans, Andziak said.

First, the researchers compared the ratio of reduced glutathione, an antioxidant, to oxidized glutathione. As the body uses up its reduced glutathione to fight oxidative stress, the pool of oxidized glutathione increases. This ratio of reduced to oxidized glutathione is thus an indicator of oxidative stress: the greater the ratio, the less oxidative stress has occurred. The oxidative stress theory predicts that in naked mole-rats this ratio will be higher than in mice.

When the researchers measured this ratio in the liver, they found that the opposite was true. Mole-rats had less reduced glutathione and thus a lower ratio, indicating the mole-rat experienced much more oxidative stress. These results fit with the findings of a previous study in which Andziak found that naked mole-rats did not have superior antioxidant capacity when compared to mice. Mole-rats had much lower activity of the ubiquitous antioxidant enzyme, cellular glutathione peroxidase.

Mole-rat shows greater oxidative damage

The researchers next looked at how much damage the oxidation had caused. It is possible, they reasoned, that the mole-rat suffers greater oxidative stress, but its physiology had somehow prevented damage from occurring.

The researchers measured oxidative damage in lipids, DNA and proteins and found that naked mole-rats showed much greater levels of damage to each of these biological molecules, in all tissues assayed, when compared to mice. The study found multiple signs of lipid damage: The level of isoprostanes found in the urine was 10 times higher in the naked mole-rat, the level of malondialdehyde in liver tissue was twice as high and isoprostane levels in heart tissue was two-and-a-half times the level of the mice.

The researchers found significantly more protein damage in the kidney and in the heart. DNA damage was greater in the kidney and liver.

"All of the classical measures of oxidative stress are higher in the mole-rat," Andziak concluded. "Given that naked mole-rats live an order of magnitude longer than predicted based on their body size, our findings strongly suggest that mechanisms other than attenuated oxidative stress may explain the impressive longevity of this species."

Next steps

The next step is to determine how the mole-rats manage to live with the damage caused by oxidative stress. Buffenstein said she suspects that the mole-rat is able to fend off the occasional oxidative insult that can occur, and that may be more important than what happens with the steady-state levels of oxidative stress that result from normal metabolic activity.

Buffenstein theorizes that the naked mole-rats in her laboratory suffer higher levels of oxidative stress than they would in their natural underground habitat, where they encounter much lower levels of oxygen. But this exposure at an early age may provide some protection against acute oxidative stress and may be of considerable importance in their resistance to bursts oxidative stressors throughout their lives, she said.

"The naked mole-rat, with its surprisingly long lifespan and remarkably delayed aging, seems like the perfect model to provide answers about how we age and how to retard the aging process," Buffenstein said. "This animal may one day provide the clues to how we can significantly extend life."

APS provides a wide range of research, educational and career support and programming to further the contributions of physiology to understanding the mechanisms of diseased and healthy states. In 2004, APS received the Presidential Award for Excellence in Science, Mathematics and Engineering Mentoring.

11:50 07 October 2006

Within a decade Australians will be able to find out how good their genes are at fighting disease, which environmental risks they are susceptible to and steps they should take to prevent the onset of ill-health. And by the turn of the century it will be commonplace to have a bad combination of genes repaired to avoid disease.

'Then, Now…Imagine', a new report compiled by Research Australia in consultation with 10 of the country's leading health and medical researchers including two Nobel Prize winners and four Australians of the Year, predicts individual gene profiling from blood samples will revolutionise healthcare within ten years.

2006 Australian of the Year, Professor Ian Frazer, who discovered the technology that led to the newly released cervical cancer vaccine, said the upshot will be the ability to develop personalised healthcare plans – a roadmap for health from the day of birth.

"Doctors will be able to predict what health problems we might get so we can take appropriate precautions. They will also be able to assess what treatments will work best on an individual basis to achieve optimum health results. Long-term it will be possible to avoid certain diseases altogether through gene therapy," he said.

Sponsored by MBF, the report has been released by Research Australia to commemorate "Thank You" Day (14 November 2006), Australians' annual opportunity to send personal messages of appreciation to medical researchers whose work is special to them via www.thankyouday.org or 0428THANKS. "Thank You" Day is held each year with the support of the Macquarie Bank Foundation.

Five other

key forecasts are:

- Growing new body parts

- Smart drugs

- A Raft of New Vaccines

Therapeutic vaccines are also well advanced in development and involve re-educating the immune system to recognise cancer cells as intruders and attack them.

And over the next few decades we are likely see vaccines for many viral infections like HIV/AIDS and Hepatitis C, and for major diseases like diabetes. In fact Melbourne's Diabetes Vaccine Development Centre is about to start clinical trials for a new vaccine for Type 1 Diabetes.

- Building New Nerve Pathways

This technology will also be applied to other disabilities. We will be able to reconnect electrical wiring in damaged spinal columns, stimulate nerve growth and allow messages to be relayed to the brain. Further into the future, this could ultimately allow quadriplegics and paraplegics to walk again. Other applications are likely to include correcting the faulty circuits that create epileptic episodes and creating transport systems for slow release of insulin to diabetics.

- Operating before birth

--------------------------------------

You can download the

full 'Then, Now…Imagine' Report from www.thankyouday.org.

From 9 October until 17 November you can also send you personal message

of thanks to Australia's health and medical researchers via the website

or you can text it to 0428THANKS.

Scientists Who

Contributed To 'Then, Now…Imagine'

Dr Robin Warren, Nobel Laureate 2005 - with Barry

Marshall,

proved a bacteria called helicobacter pylori caused gastritis and

stomach ulcers and that most ulcers could be permanently cured with

antibiotics. Professor Peter Doherty, Nobel Laureate 1996 – Discovered that T-cells, the foot soldiers in our bloodstream, were expert at killing cells that had viruses locked inside. This has led to new and better vaccines, healthy organ transplants and better treatment of conditions like Multiple Sclerosis and Diabetes.

Professor Ian Frazer, Australian of the Year 2006 – Gained international fame for developing the world's first vaccine to combat cervical cancer.

Dr Fiona Wood, Australian of the Year 2004 - Headed up the team of doctors who treated the burns victims of the 2002 Bali bombing. Her use of 'spray on skin' sped up the recovery process for those who had suffered horrific burns.

Professor Fiona Stanley, Australian of the Year 2003 - With Carol Bower, as part of an international collaboration, discovered the link between folate intake and spina bifida. This led to women being advised to increase folate intake before and during pregnancy and supplementation of some foods with folate.

Sir Gustav Nossal, Australian of the Year 2000 – Discovered the magic 'one cell-one antibody' rule which led to the development of effective new therapies for heart disease, breast cancer and severe arthritis.

Professor Terry Dwyer - Led the team which proved the link between a baby's sleeping position and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. They found that a baby sleeping on its stomach has ten times the risk of SIDS than babies who sleep in other positions.

Professor Graeme Clark - Pioneered the multiple-channel cochlear implant which has brought hearing and speech understanding to tens of thousands of people with severe-to-profound hearing loss in more than 70 countries.

Professor Judith Whitworth – Discovered how steroids raise blood pressure. Former Chief Medical Officer for the Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services and current Chair of the World Health Organisation (WHO) Global Advisory Committee on Health Research.

Professor John Shine – First to clone a human hormone gene and discovered a gene sequence, the Shine-Dalgarno sequence, which is important for the control of protein synthesis. Former Chair of the National Health and Medical Research Council and current member of the Prime Minister's Science, Engineering & Innovation Council.

Research Australia is a unique national alliance of more than 180 member and donor organisations with a common mission to make health and medical research a higher national priority. For more information on Research Australia visit www.researchaustralia.org.

Some

patients stop needing

antidepressant medication after having plastic surgery

Study presented at American Society of Plastic Surgeons annual meeting

SAN FRANCISCO – It has been proven that plastic surgery can

improve

self-esteem, but can it also act as a natural mood enhancer? A

significant number of patients stopped taking antidepressant medication

after undergoing plastic surgery, according to a study presented today

at the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) Plastic Surgery 2006

conference in San Francisco.

Study presented at American Society of Plastic Surgeons annual meeting

"Plastic surgery patients are taking a proactive approach in making themselves happier by improving something that has truly bothered them," said Bruce Freedman, MD, ASPS Member Surgeon and study author. "While we are not saying that cosmetic plastic surgery alone is responsible for the drop in patients needing antidepressants, it surely is an important factor."

In the study, 362 patients had cosmetic plastic surgery – 17 percent or 61 patients were taking antidepressants. Six months after surgery, however, that number decreased 31 percent, down to 42 patients. In addition, 98 percent of patients said cosmetic plastic surgery had markedly improved their self-esteem.

All of the patients, who were primarily middle-aged women, had an invasive cosmetic plastic surgery procedure such as breast augmentation, tummy tuck or facelift. The authors did not identify any other major life changes that may have affected patients' use of antidepressants.

"We have just begun to uncover the various physical and psychological benefits of plastic surgery," said Dr. Freedman. "By helping our patients take control over something they were unhappy about, we helped remove a self-imposed barrier and ultimately improved their self-esteem."

-------------------------------

For referrals to ASPS Member Surgeons certified by the

American

Board of Plastic Surgery, call 888-4-PLASTIC (475-2784) or visit www.plasticsurgery.org

where you can also learn more about cosmetic and reconstructive plastic

surgery.

The American Society of Plastic Surgeons is the largest organization of board-certified plastic surgeons in the world. With more than 6,000 members, the society is recognized as a leading authority and information source on cosmetic and reconstructive plastic surgery. ASPS comprises 94 percent of all board-certified plastic surgeons in the United States. Founded in 1931, the society represents physicians certified by The American Board of Plastic Surgery or The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada.

Note: The study "Cosmetic Surgery and the Use of Antidepressant Medication" is being presented in electronic format, Sunday, Oct. 8 – Tuesday, Oct. 10, at the Moscone Convention Center, San Francisco. Reporters can register to attend Plastic Surgery 2006 and arrange interviews with presenters by logging on to www.plasticsurgery.org/news_room/Registration.cfm or by contacting ASPS Public Relations at (847) 228-9900 or in San Francisco, Oct. 7-11 at (415) 905-1730.

Compelling

evidence demonstrates

that 'Hobbit' fossil does not represent a new species of hominid

Most complete, interdisciplinary study published on raging controversy about fossil found in Flores, Indonesia

CHICAGO --

What may well turn out to

be the definitive work in a debate that has been raging in

palaeoanthropology for two years will be published in the November 2006

issue of Anatomical Record. Most complete, interdisciplinary study published on raging controversy about fossil found in Flores, Indonesia

The new research comprehensively and convincingly makes the case that the small skull discovered in Flores, Indonesia, in 2003 does not represent a new species of hominid, as was claimed in a study published in Nature in 2004. Instead, the skull is most likely that of a small-bodied modern human who suffered from a genetic condition known as microcephaly, which is characterized by a small head.

"It's no accident that this supposedly new species of hominid was dubbed the 'Hobbit;'" said Robert R. Martin, PhD, Curator of Biological Anthropology at the Field Museum and lead author of the paper. "It is simply fanciful to imagine that this fossil represents anything other than a modern human." The new study is the most wide-ranging, multidisciplinary assessment of the problems associated with the interpretation of the 18,000-year-old Flores hominid yet to be published. The authors include experts on:

- scaling effects of body size, notably with respect to the brain: Dr. Martin and Ann M. MacLarnon, PhD, School of Human & Life Sciences, Roehampton University in London;

- clinical and genetic aspects of human microcephaly: William B. Dobyns, PhD, Department of Human Genetics, University of Chicago; and

- stone tools: James Phillips, PhD, Departments of Anthropology at the University of Illinois at Chicago and the Field Museum.

Significantly, the second most recent publication to conclude that the "Hobbit" was microcephalic--another multidimensional study that was published in the September 5, 2006, issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences--includes a co-author who was also a co-author of the original publication in Nature. That scientist, R.P. Soejono of the National Archaeological Research Center in Jakarta, Indonesia, now writes that the Flores hominid was microcephalic rather than a new hominid species.

|

|

| Skull cast and cast of the endocranial cavity (endocast) from the Royal College of Surgeons in London of a modern adult human who suffered from microcephaly. It is strikingly similar to the following skull and endocast of a 32-year-old microcephalic woman. Together, the two specimens provide evidence that the LB1 skull from Flores, which is so similar to these two specimens, could also have been a microcephalic adult. Photo by John Weinstein, Courtesy of The Field Museum (Negative # Z94438_07Ad) | Skull cast and cast of the endocranial cavity (endocast) from a 32-year old woman who had the body size of a 12-year-old child. She lived in Lesotho, a county in Southern Africa, and these casts are part of The Field Museum's collection (Accession Nos. A219679 And A219680). This specimen and the one above have a relatively normal exterior appearance despite their very small size. Together they demonstrate that the LB1 skull from Flores could also have been an adult who suffered from microcephaly. Photo by John Weinstein, Courtesy of The Field Museum (Negative # Z94438_01Ad) |

The starting point for the new research in Anatomical Record was the realization that the brain of the Flores skull (at 400 cc, the size of a grapefruit and less than one-third of the normal size for a modern human) is simply too small to fit anything previously known about human brain evolution. In addition, the stone tools found at the same site include types of tools that have only been reported for our own species, Homo sapiens.

Brain size of the Flores hominid, originally called Homo floresiensis, is known only from the main specimen discovered there, the LB1 skeleton. Skeletal fragments have been attributed to eight other individuals, but nothing can be said about their brain sizes. (They are small-bodied, but that has never been at issue.)

The new exhaustive research shows that the LB1 brain is simply too small to have been derived from H. erectus by evolutionary dwarfing, as was claimed by those wh

o

discovered it. In fact, the size

of the brain corresponds very closely to the average value for modern

human microcephalics. Microcephaly is a term that covers many

conditions. There are more than 400 different human genes for which

mutations can result in small brain size. Accordingly, there is a

correspondingly wide range of different syndromes that are recognized

in clinical practice. Many syndromes involve pronounced deficits

("low-functioning microcephaly"), but some have milder effects

("high-functioning microcephaly"), permitting survival into adulthood

and a surprising degree of behavioral competence in certain cases.

Microcephaly is often associated with severely reduced stature, but

some microcephalics have relatively normal body size.

o

discovered it. In fact, the size

of the brain corresponds very closely to the average value for modern

human microcephalics. Microcephaly is a term that covers many

conditions. There are more than 400 different human genes for which

mutations can result in small brain size. Accordingly, there is a

correspondingly wide range of different syndromes that are recognized

in clinical practice. Many syndromes involve pronounced deficits

("low-functioning microcephaly"), but some have milder effects

("high-functioning microcephaly"), permitting survival into adulthood

and a surprising degree of behavioral competence in certain cases.

Microcephaly is often associated with severely reduced stature, but

some microcephalics have relatively normal body size. Because the LB1 skeleton is clearly that of an adult, it should obviously be compared with "high-functioning" modern human microcephalics rather than with "low-functioning" microcephalics who died early. The new study shows that skulls and brain casts from two modern human microcephalics who survived into adulthood are actually quite similar to those of the LB1 specimen. This supports the likelihood that LB1 was microcephalic.

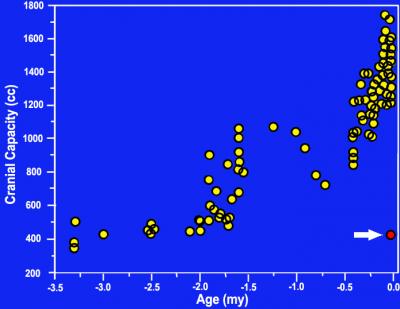

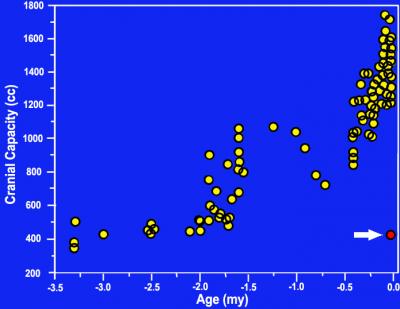

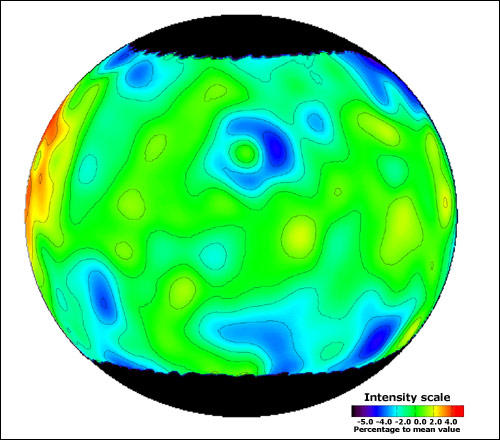

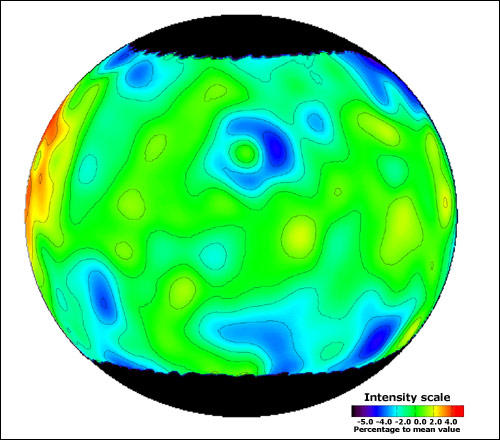

This

graph shows the cranial capacities in cubic centimeters for 118 fossil

hominids plotted against time, extending back almost 3.5 million years.

The arrow indicates the highly incongruous value reported in Nature by

Brown et al. in 2004 for H. floresiensis, described as an insular dwarf

derived from Homo erectus. The relatively tiny brain size only 18,000

years ago does not fit into known patterns of hominid brain size and

development. It is "off the chart." Graph by

Robert D. Martin, Courtesy of The Field Museum

Also, it has been claimed that LB1 had unusually large teeth

("megadonty"). However, it turns out that the teeth are not

particularly large, after allowing for the expected effect of dwarfing.

They are actually closely similar in size to those of a modern human

microcephalic. Another area of controversy concerns the stone tools discovered in association with the Flores fossils. Initially, the discoverers claimed that the tools were sophisticated, as indeed they are. More recently, continuity has been claimed with tools from Mata Menge on Flores that are purportedly 800,000 years ago. This is simply implausible, according to the authors of the new research.

"Nobody has even claimed cultural continuity in stone tool technology over such a long period (800,000 to 18,000 years ago)," Dr. Phillips said. "To do so ignores the significance of tools found with the LB1 skeleton that were made with the advanced prepared-core technique, otherwise confined to Neanderthals and modern humans."

There has been too much media hype and not enough sound scientific evaluation surrounding this discovery, Dr. Martin concluded. "Science needs more balance and less acrimony as we continue to unravel this discovery."

________________

•

Robert D. MartinRobert D. Marin, PhD, Curator of Biological Anthropology at The Field Museum, has devoted his career to studying primate development and evolution. In his quest to achieve a reliable reconstruction of primate evolutionary history, Dr. Martin has studied an extensive array of characteristics in the living species, including anatomical features, physiology, chromosomes and DNA. Dr. Martin has been particularly interested in the brain and reproductive biology, as these systems have been of special importance in primate evolution. With skeletal features, it is possible to include the fossil evidence and thus to include geological time in the picture. By studying living primates in the field in the forests of Africa, Madagascar, Brazil and Panama, Dr. Martin has also been able to include behavior and ecology in an overall synthesis. That synthesis was first presented in his textbook Primate Origins and Evolution, published by Princeton University Press in 1990. Since then, he has been working on refinements in several different directions. Photo by John Weinstein, Courtesy of The Field Museum (Negative # GN90075_36Ac)

• Jim Phillips

James Phillips, PhD, Departments of Anthropology at the University of Illinois at Chicago and the Field Museum, is an expert on stone tools. Initially, the discoverers of the Flores fossils claimed that the tools found in association with the fossils were sophisticated, as indeed they are. More recently, continuity has been claimed with tools from Mata Menge on Flores that are purportedly 800,000 years ago. This is simply implausible, according to the authors of the new research. "Nobody has even claimed cultural continuity in stone tool technology over such a long period (800,000 to 18,000 years ago)," Dr. Phillips said. "To do so ignores the significance of tools found with the LB1 skeleton that were made with the advanced prepared-core technique, otherwise confined to Neanderthals and modern humans."

Insurance

companies deny

medically necessary breast reductions based on random, unproven criteria

Study Presented at American Society of Plastic Surgeons annual Meeting

SAN FRANCISCO – What

if you couldn't perform daily activities, such

as exercising or running with your children, because of overly large

breasts that caused unending pain? Despite existing scientific studies

that outline the medical necessity for breast reduction, many insurance

companies are denying thousands of women the procedure each year

because of rigid, unfounded conditions to secure coverage, according to

a study presented today at the American Society of Plastic Surgeons

(ASPS) Plastic Surgery 2006 conference in San Francisco.

Study Presented at American Society of Plastic Surgeons annual Meeting

"People often think breast reduction is an elective cosmetic procedure, but the majority of women seeking this surgery are legitimately debilitated by their breasts," said Michael Wheatley, MD, ASPS Member Surgeon and paper co-author. "The criteria most insurance companies use is not supported by medical literature and eliminates a large number of women from coverage, forcing them to fend for themselves."

Most insurance companies require patients to exhibit specific signs and symptoms prior to approving breast reduction as medically necessary. The amount of tissue removed to relieve symptoms associated with overly large breasts is the most controversial of all insurance criteria.

The authors reviewed the breast reduction policies of 87 health insurance companies. Despite contrary medical studies, 85 companies require a minimum amount of tissue to be removed to cover the procedure – 49 of these companies require a minimum amount to be removed independent of the patient's height and weight.

According to published studies, although most patients have a one-and-a-half to two cup size reduction, the amount of tissue removed, body weight, level of obesity, or bra cup size do not affect the benefits that patients receive from breast reduction.

Many insurance companies require that patients exhibit all of the following symptoms to receive coverage for breast reduction: back, neck, shoulder, and arm pain; rashes; bra strap grooves; and numbness in the upper torso. The authors found that while most patients suffer from many of these symptoms, rarely do they exhibit all.

According to Dr. Wheatley, most patients are women between 30 and 50 years old who have had upper skeletal pain for years. Many of them have tried various treatments, including physical therapy and pain medications, to manage the pain before turning to breast reduction. However, many of these women are still turned away by their insurance companies.

According to ASPS statistics, more than 114,000 breast reductions were performed in 2005.

-----------------------------------

For referrals to ASPS Member Surgeons certified by the

American

Board of Plastic Surgery, call 888-4-PLASTIC (475-2784) or visit www.plasticsurgery.org

where you can also learn more about cosmetic and reconstructive plastic

surgery.

The American Society of Plastic Surgeons is the largest organization of board-certified plastic surgeons in the world. With more than 6,000 members, the society is recognized as a leading authority and information source on cosmetic and reconstructive plastic surgery. ASPS comprises 94 percent of all board-certified plastic surgeons in the United States. Founded in 1931, the society represents physicians certified by The American Board of Plastic Surgery or The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada.

Note: The study "Reduction Mammoplasty: A Review of Managed Care Medical Policy Criteria" is being presented Sunday, Oct. 8, 3:04 p.m., at the Moscone Convention Center, San Francisco. Reporters can register to attend Plastic Surgery 2006 and arrange interviews with presenters by logging on to www.plasticsurgery.org/news_room/Registration.cfm or by contacting ASPS Public Relations at (847) 228-9900 or in San Francisco, Oct. 7-11 at (415) 905-1730. VIRGINIA BEACH, VA (October 9, 2006) -- The long-lived naked mole-rat shows much higher levels of oxidative stress and damage and less robust repair mechanisms than the short-lived mouse, findings that could change the oxidative stress theory of aging.

The new study comparing the naked mole-rat, which has a life span of 28 years, and the mouse, which has a lifespan of three years, will be presented Oct. 8 at The American Physiological Society conference, Comparative Physiology 2006: Integrating Diversity. The results fly in the face of the oxidative stress theory of aging, which holds that damage caused by oxidative stress is a significant contributor to the aging process.

Under this theory, naked mole-rats should be better at preventing or repairing oxidative stress than their much shorter-lived cousin, the mouse. The study, "High oxidative damage levels in the longest-living rodent, the naked mole-rat," was done by Blazej Andziak and Rochelle Buffenstein, of The City College of New York, Timothy P. O'Connor, of Weill Medical College of Cornell University, and Asish P. Chaudhiri and Holly Van Remmen of the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio. The study was presented during a poster session on October 8.

Don't toss the oxidative stress theory of aging out the window just yet, but prepare to modify it, said Buffenstein, the senior author. Her team suspects that the naked mole-rat's longevity stems from its ability to defend against acute bouts of oxidative stress. That is, the kind of oxidation that happens because of an unusual occurrence rather than the kind that happens as a result of normal aerobic respiration.

For example, when hydrogen peroxide is added to a culture containing naked mole-rat fibroblast cells, they remain viable and appear to repair the acute damage more rapidly than shorter-lived animals, explained Buffenstein.

What is old age?

We know that all organisms age and die. It's such an inevitable course of events that most of us spend more time thinking about how to hide the wrinkles and gray hair than we do about what our cells are actually doing to usher us to the end. Physiologists are looking at molecules and cells to understand this process.

One way to look at aging is to compare closely related organisms with different life spans. That's why it made sense to compare mole-rats and mice: They're the same size and they're rodents, but the mole-rat lives to 28 years, about nine-times longer than the mouse.

"Mole-rats must have something happening at the biochemical level to allow them to do this," said Andziak, the study's lead author. Specifically, he wanted to see if oxidative stress could explain the difference.

Oxidative stress occurs during metabolism when oxygen (O2) splits into single oxygen atoms, known as free radicals. These oxygen atoms may circulate by themselves, or combine with other atoms and molecules to form reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS can damage DNA, lipids and proteins thus impairing normal cellular function. Antioxidants help to neutralize ROS, thus restricting the potential of ROS to damage biological molecules.

Mole-rat has more oxidative stress

The study compared two-year-old naked mole-rats to four-month-old mice. The researchers chose those ages so that the animals would be equivalent ages relative to their maximum lifespans, Andziak said.

First, the researchers compared the ratio of reduced glutathione, an antioxidant, to oxidized glutathione. As the body uses up its reduced glutathione to fight oxidative stress, the pool of oxidized glutathione increases. This ratio of reduced to oxidized glutathione is thus an indicator of oxidative stress: the greater the ratio, the less oxidative stress has occurred. The oxidative stress theory predicts that in naked mole-rats this ratio will be higher than in mice.

When the researchers measured this ratio in the liver, they found that the opposite was true. Mole-rats had less reduced glutathione and thus a lower ratio, indicating the mole-rat experienced much more oxidative stress. These results fit with the findings of a previous study in which Andziak found that naked mole-rats did not have superior antioxidant capacity when compared to mice. Mole-rats had much lower activity of the ubiquitous antioxidant enzyme, cellular glutathione peroxidase.

Mole-rat shows greater oxidative damage

The researchers next looked at how much damage the oxidation had caused. It is possible, they reasoned, that the mole-rat suffers greater oxidative stress, but its physiology had somehow prevented damage from occurring.

The researchers measured oxidative damage in lipids, DNA and proteins and found that naked mole-rats showed much greater levels of damage to each of these biological molecules, in all tissues assayed, when compared to mice. The study found multiple signs of lipid damage: The level of isoprostanes found in the urine was 10 times higher in the naked mole-rat, the level of malondialdehyde in liver tissue was twice as high and isoprostane levels in heart tissue was two-and-a-half times the level of the mice.

The researchers found significantly more protein damage in the kidney and in the heart. DNA damage was greater in the kidney and liver.

"All of the classical measures of oxidative stress are higher in the mole-rat," Andziak concluded. "Given that naked mole-rats live an order of magnitude longer than predicted based on their body size, our findings strongly suggest that mechanisms other than attenuated oxidative stress may explain the impressive longevity of this species."

Next steps

The next step is to determine how the mole-rats manage to live with the damage caused by oxidative stress. Buffenstein said she suspects that the mole-rat is able to fend off the occasional oxidative insult that can occur, and that may be more important than what happens with the steady-state levels of oxidative stress that result from normal metabolic activity.

Buffenstein theorizes that the naked mole-rats in her laboratory suffer higher levels of oxidative stress than they would in their natural underground habitat, where they encounter much lower levels of oxygen. But this exposure at an early age may provide some protection against acute oxidative stress and may be of considerable importance in their resistance to bursts oxidative stressors throughout their lives, she said.

"The naked mole-rat, with its surprisingly long lifespan and remarkably delayed aging, seems like the perfect model to provide answers about how we age and how to retard the aging process," Buffenstein said. "This animal may one day provide the clues to how we can significantly extend life."

---------------------------------------

The American Physiological Society was founded in 1887 to

foster

basic and applied bioscience. The Bethesda, Maryland-based society has

10,500 members and publishes 14 peer-reviewed journals containing

almost 4,000 articles annually. APS provides a wide range of research, educational and career support and programming to further the contributions of physiology to understanding the mechanisms of diseased and healthy states. In 2004, APS received the Presidential Award for Excellence in Science, Mathematics and Engineering Mentoring.

11:50 07 October 2006

Corals may be vulnerable to

the same processes

that cause tooth decay in humans. Healthy coral lives symbiotically

with single-celled algae, but fleshy macroalgae spreading over reefs,

usually as a result of pollution, can spell trouble.

Now Jennifer Smith of the University of California, Santa Barbara, has shown that sugars released by the algae diffuse into the coral and fertilise bacteria, making them pathogenic. "Algae can indirectly cause coral mortality by enhancing microbial activity," she says.

Smith and her colleagues took coral and algae from reefs off the Line Islands in the south Pacific and placed them in adjacent chambers separated by a 0.02-micrometre filter. This prevented the passage of microbes and viruses but allowed the diffusion of dissolved sugars. All the coral died. When the experiment was repeated, this time with the addition of ampicillin, a broad-spectrum antibiotic, all the coral survived. Smith presented the results at the International Society of Reef Studies in Bremen, Germany, last month.

"The work highlights another potential mechanism by which macroalgal-dominated reefs could persist and reduce the likelihood of switching back to a coral-dominated state," says Peter Mumby of the University of Exeter, UK.

Even so, the veteran Air National Guard pilot did a double-take the first time he saw what appeared to be a Muslim cemetery and a mound of ruins on Range 48 at the U.S. Army's Fort Drum in upstate New York.

"It looked just like way it looked over there. It's going to give our pilots some firsthand experience in recognizing and identifying these kinds of sites from the air under fairly realistic conditions," said Mitchell, of Merrimac, N.H., who flies with the 118th Fighter Wing out of Connecticut.

"You don't want to be dropping bombs on cemeteries and mosques, or blow up some important historical site that's been there for thousands of years," said Mitchell. "That's certainly not going to make us any friends."

That's the thinking of archaeologist Laurie Rush, Fort Drum's cultural resources manager.

So with $165,000 in funding from the Department of Defense Legacy Program, Rush and the post's Integrated Training Area Management unit has begun to heighten the cultural sensitivity of the soldiers and pilots who train at Fort Drum, including building mock cemeteries and archaeological ruins and developing a field guide.

"We need to get them trained before the fact, not after the damage is done. This should be part of deployment training for anywhere in the world - becoming familiar with the region's cultural heritage," said Rush.

Rush, who's been at Fort Drum eight years, said she felt compelled to develop an awareness program after the British Museum last year reported the defiling of the ancient city of Babylon in 2003 by invading U.S. Marines, who damaged and contaminated artifacts dating back thousands of years. Transgressions included building a helicopter pad on the city's ruins, destroying a 2,600-year-old brick road and filling sandbags with archaeological fragments.

"Museum professionals around the world were horrified. I was so angry, too, because it was just needless," Rush said.

Fort Drum, located near the U.S.-Canadian border, has a rich archaeological history with dozens of American Indian sites spread throughout the sprawling 105,000-acre post. As a result, 10th Mountain Division and other troops training at Fort Drum already receive an atypical exposure to archaeological and cultural issues, Rush said.

But she realized a few years ago that officials were practicing a "keep out" mentality that was counterproductive.

"Here we are barring them from the sites at Fort Drum, and then asking them to occupy a World Heritage site in a responsible way having failed to teach them how to act in a responsible way," she said.

So Rush's small staff took steps to preserve Sterlingville, one of six North Country communities erased by the federal government in 1941 so it could expand Fort Drum. The site is a National Registered Archaeological District. There, a civilian crew capped part of the site with geotextiles and recycled tank treads to protect it. The ruins are marked by signs carrying the international designation for an archaeology site.

Soldiers don't receive any formal instruction about archaeology but they regularly train at the site.

"At this point, we're hoping that if a situation arises while they are field, they will remember what they saw here at Fort Drum. Maybe they don't remember exactly what to do but they remember at least that the site needs protection," she said, adding that soldiers' top priority must be defending themselves.

Range 48 is a wilderness area in the middle of the post used for live-fire target practice. Strewn across the landscape are the burnt skeletons of tanks, cannons and military vehicles. There's also a mock Scud missile launcher.

Across the road, less than a hundred yards away from one target area, sit the fake ruins and cemetery that Rush and her staff built using concrete, plywood and paint. The cylindrical ruins are modeled after ruins in Uruk that are believed to be 4,000 to 5,000 years old. Rush's crew plans to soon add a mosque.

On another range used for infantry training, a second fake Muslim cemetery and another set of ruins are set up just outside a small fabricated village. The cemetery sits on a bend in the road in a spot that affords good fighting position, Rush said.

Like they are in the Middle East, the markers are plain, unadorned and face toward Mecca. Arabic blessings are imprinted into the concrete in the walls of the ruins.

"This helps trains soldiers to immediately identify cultural features so troops don't waste valuable time during combat operations," she said.

She recounts one incident where a commanding officer had his troops put up a communications tower on the top of a pile of rubble, not realizing it was a tell - an artificial mound covering the successive remains of ancient communities. The unit started erecting a security fence when they began digging up artifacts. They had to stop, take down the fence and move the tower.

To be effective, different types of soldiers need to be trained differently, said Rush. Soldiers who drive tanks and trucks will need training different from that given infantryman.

"MPs, for instance, will need to know how to look for artifacts and be trained in luggage screening techniques," she said.

The US-based X-Prize Foundation is offering what it says is the largest medical prize in history - $10m - for the first private team that can decode 100 human genomes in 10 days.

Organisers say rapid genetic sequencing is science's next great frontier, and will usher in a new era of personalised medicine, allowing doctors to determine patients' susceptibility to illness and the genetic links to diseases such as cancer and Alzheimer's.

The Archon X- Prize

for Genomics is the second major challenge from the foundation, which

in 2004 awarded $10m to the team behind the private manned spacecraft

SpaceShipOne.

Prize

for Genomics is the second major challenge from the foundation, which

in 2004 awarded $10m to the team behind the private manned spacecraft

SpaceShipOne.

It currently costs millions of dollars and takes many months to sequence an individual's genome, encoded in DNA. Tests of certain genes are already helping doctors select treatments and therapies for individual patients.

Ethical controversy

Yet scientists say the real benefits to mankind will only come when a much larger sampling of genetic information is available to help decipher the environmental and hereditary aspects of disease.

Dr J Craig Venter - one of the scientists behind the first sequencing of the human genetic code - is on the X-Prize's scientific advisory board.

Adenine (A) bonds with thymine (T); cytosine(C) bonds with guanine (G)

These "letters" form the "code of life"; there are about 2.9 billion base-pairs in the human genome wound into 24 distinct bundles, or chromosomes

Written in the DNA are about 20-25,000 genes which human cells use as starting templates to make proteins; these sophisticated molecules build and maintain our bodies"We need a database of millions of human genomes to help us fully decipher the nature and nurture aspects of human existence," he said.

Yet - as the foundation acknowledges - this is a controversial area of research fraught with ethical, legal and social implications.

Public concerns about information privacy, and fears of future discrimination based not on race or class, but genetics, are already said to be slowing research at a significant rate.

Dr Francis Collins, head of the Human Genome Research Institute, said: "There are real questions here of the benefits versus the risks. We need appropriate protections for people, and we need the public to engage in a policy debate."

Almost three years ago, the US Senate passed legislation specifically banning employers and insurers from discriminating against people based on the results of genetic tests.

But this Genetic Non-Discrimination bill is currently stalled in the House of Representatives. There are hopes that the X-Prize will help push the bill to completion.

As a follow-up to the competition, the winning team will be paid to map the genetic sequences of the "Genome 100" - a group of celebrities, benefactors and members of the public.

That group already includes Dr Stephen Hawking, CNN's Larry King; and Anousheh Ansari, the world's first female "space tourist", whose family funded the original X-Prize for the first private manned spaceflight.

Following on from the success of the original Ansari prize, the X-Prize Foundation intends to launch two prizes per year. The next launch is expected in early 2007.

The foundation describes itself as an educational, non-profit prize institute that aims to bring about "radical breakthroughs in space and technology for the benefit of humanity".

Archon Minerals is the title sponsor of the Archon X-Prize for Genomics after a multi-million dollar donation by the company's president, Dr Stewart Blusson. Story from BBC NEWS: http://news.bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/-/2/hi/science/nature/5404678.stm

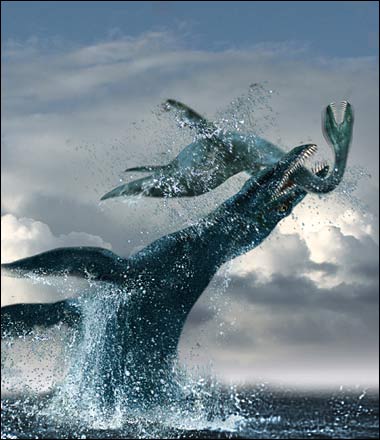

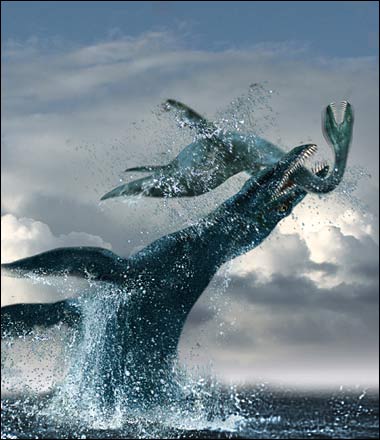

The finds belong to two groups of extinct marine reptiles - the plesiosaurs and the ichthyosaurs.

One skeleton has been nicknamed The Monster because of its enormous size.

These animals were the top predators living in what was then a relatively cool, deep sea.

Palaeontologists from the University of Oslo's Natural History Museum discovered the fossils during fieldwork in a remote part of Spitsbergen, the largest island in the Svalbard archipelago.

Jorn Harald Hurum, co-director of the dig, said he was taken aback by the sheer density of fossil remains in one area.

"You can't walk for more than 100m without finding a skeleton. That's amazing anywhere in the world," he told BBC News.

Dr Dave Martill, a palaeontologist at the University of Portsmouth, UK, commented: "These sites are very unusual. To find that many individuals is a remarkable thing - that's a bonanza."

Ichthyosaurs bore a passing resemblance to modern dolphins, but they used an upright tail fin to propel themselves through the water.

Plesiosaurs are said to fit descriptions of Scotland's mythical Loch Ness monster. They used two sets of powerful flippers for swimming and came in two varieties - one with a

small head and very long neck, and another with a large head and short

neck.

with a

small head and very long neck, and another with a large head and short

neck.

The short-necked varieties are known as pliosaurs.

The discovery of a gigantic pliosaur, nicknamed The Monster, was one of the most remarkable discoveries of the expedition.

Its skeleton has dinner-plate-sized neck vertebrae, and the lower jaw has teeth as big as bananas.

Tooth in the neck

The skeleton is not yet fully excavated, but its skull is about 3m long, suggesting the body could be more than 8m from the tip of its nose to its tail.

"What's amazing here is that it looks like we have a complete skeleton. No other complete pliosaur skeletons are known anywhere in the world," said Dr Hurum.

The researchers even found evidence of an attack on one of the creatures. An ichthyosaur tooth is embedded in a neck vertebra from one plesiosaur belonging to the genus Kimmerosaurus .

The fossil hoard comprises 21 long-necked plesiosaurs, six ichthyosaurs and one short-necked plesiosaur. The bones were unearthed in fine-grained sedimentary rock called black shale.

"Everything we're finding is articulated. It's not single bones here and there, and bits and pieces - these are complete skeletons," said Dr Hurum.

After death, the carcasses came to rest in mud at the bottom of the deep ocean, where little or no oxygen was present.

Dr Hurum said an unusual chemistry of the mud could have been responsible for the remarkable preservation of the specimens: "Something happened with the chemistry that's really good for bone preservation. Some skeletons are pale white even though they're in black shale - they look like 'roadkill'."

Artist's interpretation of "The Monster" catching a smaller plesiosaur. (Artwork: Tor Sponga, BT)

The marine reptiles found in the Norwegian archipelago are very similar to ones known from southern England. Dr Hurum said the animals could have been living in the same ocean and he now plans to compare the Arctic finds with those from Britain.

The Svalbard excavation was led by Dr Hurum and Hans Arne Nakrem, also of Oslo's Natural History Museum. The museum plans to return to the field site in the summer of 2007 to resume excavations.

Paul.Rincon-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk Story from BBC NEWS: http://news.bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/-/2/hi/science/nature/5403570.stm Published: 2006/10/05 06:21:29 GMT LOS ALAMOS, N.M., Oct. 5— The old men stared at one another through squinted eyes on Thursday and began to remember the lives they once lived.

Slowed by age and bent with frailty, about 50 veterans of the Manhattan Project gathered at the Best Western Hilltop House Hotel here as part of three days of events to commemorate their work on the atomic bomb.

Arthur Schelberg, 85, was recruited in 1943, shortly after earning a physics degree from Princeton.

“We knew what was going on before it was ever made public,” Mr. Schelberg said as the sounds of Glenn Miller blared through a hotel ballroom. “I was here from the beginning.”

Mr. Schelberg and others spent hours trading anecdotes about their work on the Manhattan Project, the initiative to develop nuclear weapons in World War II.

Operating under the Army Corps of Engineers, the project officially began in 1942 out of fears that the Nazis were creating an atomic bomb. About 125,000 people were involved in the effort around the country, with many young scientists and engineers from elite universities.

Roughly 5,000 worked here. The recently restored V Site was where scientists assembled the Trinity device, tested in 1945 over Alamogordo in the first nuclear explosion.

Daniel Gillespie, 84, worked on Trinity and other ‘Fat Man’ bombs beginning in 1944. Through a wry smile, Mr. Gillespie recalled how the Army had sent him here because of his engineering background, but he was never told why until a friend whispered the details of the mission.

“We felt like if we could perfect that bomb and stop that war, then we were doing a good thing,” he said. “We were saving lives.”

Cynthia Kelly, president of the Atomic Heritage Foundation, sponsor of the reunion, said it was born out of an effort to preserve the sites where the scientists worked after Congress authorized a cleanup of the national laboratory in the 1990’s. In the process, the foundation contacted veterans and discussed their experiences.

Although not the first such reunion here, time is increasingly precious, as a vast majority of the workers are into their 80’s, Ms. Kelly said.

“What’s happening is significant, because 20 years from now, very few, if any, of the veterans of the Manhattan Project will be alive,” she said. “So it’s important to get the oral history, the first-hand accounts.”

The average age of those at Los Alamos, considered the brain trust of the Manhattan Project, was 25, Ms. Kelly said. She estimated that 20 percent remained alive. “I’m overwhelmed and engulfed with memories,” Paul Numerof, who was in a special engineers detachment, said. “It was a tense, exciting time for all of us. I felt like I was in the presence of scientific royalty.”

Dr. Numerof recalled attending Monday night meetings led by J. Robert Oppenheimer.

Aside from nostalgia, the reunion also commemorates the restoration of Manhattan Project sites at Los Alamos. They were given a federal grant in 1999, but a forest fire in 2000 heavily damaged them.

In celebration of the restoration, the Atomic Heritage Foundation and Los Alamos Historical Society have sponsored events like bus tours of the region and talks by experts like Richard Rhodes, who wrote the prize-winning “Making of the Atomic Bomb,” and Thomas O. Hunter, director of the Sandia National Laboratories in Albuquerque.

Not everyone is completely enamored of the reunion.

Jay Coghlan, executive director of Nuclear Watch New Mexico, a watchdog group in Santa Fe, said nuclear weapons continued to be produced, in a far murkier geopolitical landscape.

“I’m not going to begrudge a bunch of old fellows as reliving their war years,” Mr. Coghlan said. “Every generation has to operate under the exigencies of their time.

“The Manhattan Project gentlemen have their reunion, their memories. But meanwhile Los Alamos is getting ready to fight the next war, in which the use of nuclear weapons is entirely possible.”

That point was not lost on Ralph Gates, 82, who helped cast explosives at Los Alamos when the Army recruited him because of his engineering studies at Vanderbilt University. Although nostalgic about Los Alamos, he also remains haunted by the power that he helped give birth to.

“I wish I could tell young people today how naïve they are,” Mr. Gates said. “We were like that, too, young and naïve. We truly believed that by building that bomb there’d never be another war.

LAWRENCE,

Kan. —

Pinching a bright orange butterfly in one hand and an adhesive tag the

size of a baby’s thumbnail in the other, the entomologist

bent

down so his audience could watch the big moment.

LAWRENCE,

Kan. —

Pinching a bright orange butterfly in one hand and an adhesive tag the

size of a baby’s thumbnail in the other, the entomologist

bent

down so his audience could watch the big moment.

“You want to lay it right on this cell here, the one shaped like a mitten,” the scientist, Orley R. Taylor, told the group, a dozen small-game hunters, average age about 7 and each armed with a net. “If you pinch it for about three seconds, the tag will stay on for the life of the butterfly, which could be as long as nine months.”

Dr. Taylor, who runs the Monarch Watch project at the University of Kansas, is using the tags to follow one of the great wonders of the natural world: the annual migration of monarch butterflies between Mexico and the United States and Canada.

The

northward migration this spring was the biggest in many years, raising

hopes of butterfly enthusiasts throughout North America. But a drought

in the Dakotas and Minnesota meant that not nearly as many butterflies

started the return trip. And without the late-summer hurricanes that

normally soak the Texas prairies and sprout the nectar-heavy

wildflowers where the monarchs refuel, many are presumably finding that

leg of the journey a death march. Dr. Taylor has already halved his

prediction for the size of the winter roosts in central Mexico, to 14

acres from 30.

The

northward migration this spring was the biggest in many years, raising

hopes of butterfly enthusiasts throughout North America. But a drought

in the Dakotas and Minnesota meant that not nearly as many butterflies

started the return trip. And without the late-summer hurricanes that

normally soak the Texas prairies and sprout the nectar-heavy

wildflowers where the monarchs refuel, many are presumably finding that

leg of the journey a death march. Dr. Taylor has already halved his

prediction for the size of the winter roosts in central Mexico, to 14

acres from 30.

Nevertheless, the 4,000-mile round trip made by millions of monarchs holds a central mystery that Dr. Taylor and a network of entomologists are trying to solve.

The butterfly that goes from Canada to Mexico and partway back lives six to nine months, but when it mates and lays eggs, it may have gotten only as far as Texas, and breeding butterflies live only about six weeks. So a daughter born on a Texas prairie goes on to lay an egg on a South Dakota highway divider that becomes a granddaughter. That leads to a great-granddaughter born in a Winnipeg backyard. Come autumn, how does she find her way back to the same grove in Mexico that sheltered her great-grandmother?

Wildebeest, in their famous migration across the Serengeti, learn by following their mothers — or aunts, if crocodiles get Mom. But the golden horde moving south through North America each fall is a throng of leaderless orphans.

Birds orient themselves by stars, landmarks or the earth’s magnetism, and they, at least, have bird brains. What butterflies accomplish with the rudimentary ganglia filling their noggins is staggering.

They are one of the few creatures on earth that can orient themselves both in latitude and longitude — a feat that, Dr. Taylor notes, seafaring humans did not manage until the 1700’s, when the clock set to Greenwich time was added to the sextant and compass.

All monarchs start migrating when the sun at their latitude drops to about 57 degrees above the southern horizon.

But those lifting off anywhere from Montana to Maine must aim themselves carefully to avoid drowning in the Gulf of Mexico or hitting a dead end in Florida. The majority manage to thread a geographical needle, hitting a 50-mile-wide gap of cool river valleys between Eagle Pass and Del Rio, Tex.

To test their ability to reorient themselves, Dr. Taylor has moved butterflies from Kansas to Washington, D.C. If he releases them right away, he said, they take off due south, as they would have where they were. But if he keeps them for a few days in mesh cages so they can see the sun rise and set, “they reset their compass heading,” he said. “The question is: How?”

The skill is crucial because of storms. For example, 1999 was a banner year for monarchs on the East Coast; they were blown there by Hurricane Floyd.